The Demographic Tragedy of Ukraine: A Second Holodomor?[1]

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may be sealing the tragic fate of a country’s demographic. Although it is unknown how this war will evolve or when and how it will end, it is already substantially impacting the population of Ukraine, in part because of Russian ambitions to seize part of Ukrainian territory. History has demonstrated that the demographic effects of a war will not only be significant during the war itself but will continue to be impactful for decades into the future. This war could be especially demographically devastating for Ukraine due to the pre-war situation: Ukraine was already experiencing a declining population, low fertility, and low life expectancy compared to its European neighbors. Although the demographic effects of this war extend beyond Ukraine’s frontiers, this article seeks to roughly quantify the effects to date as well as the potential demographic effects of this war for Ukraine.

It would be naïve to consider the demographic situation and trends as main factors defining Russia’s interest in invading Ukraine, particularly considering President Vladimir Putin’s ambitions, the complexities of historic Russia-Ukraine relations, the pre-war political situation of Ukraine, and the geopolitical role of Ukraine as a main actor in the global food supply chain, among other considerations. Accordingly, discussing the demographic survival of the country could appear irrelevant in light of ongoing events: a country being devastated by an unjustified invasion and millions of families, women, children, and older people leaving the country for survival, staying in shelters that are being bombarded without consideration, or attempting to live normally in the knowledge that nothing is secure. However, historical evidence indicates that demography has been highly relevant for Ukraine, particularly during the first half of the 20th century, when the country experienced successive “… demographic reversals almost unparalleled in modern history,”[2] including the 1932–1933 great famine, referred to as the Holodomor (death by starvation), when an estimated 4 to 5 million Ukrainians lost their lives. Had the country not experienced repeated catastrophes and emigration, the estimated size of the population in 1990 would have been 87.2 million rather than 51.6 million.[3] In a future reconstruction phase, the country will have to address an even more critical demographic situation and the effects of the massive humanitarian crisis that this invasion has created.

Russian demographic challenges as a factor of the war

From ranking fourth globally in 1950 in terms of population size, surpassed only by China, India, United States and the European Union (when considered as a whole minus Eastern Europe), Russia fell to fifth place in 1990 and ninth in 2020. It is estimated that by 2050, it will rank number 14, surpassed by 10 additional countries, all of which are developing or middle income: Nigeria, Pakistan, Indonesia, Brazil, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bangladesh, Egypt, Mexico, and the Philippines. Russia has been affected by low birth rates and stagnant mortality rates. Demographically speaking, among superpowers Russia has become a dwarf country.

Putin’s statement that he perceives himself “as being on a historic mission to rebuild the Russian Empire”[4] indicates that demographic size and growth concerns may be among the president’s considerations. At his annual press conference in 2019, Putin asserted, “We are now haunted by this”[5][6] when referring to Russia’s low birth rates. Indeed, the Russian population has been declining or only growing slowly in the last 30 years, with a prospect of a sustained decline from now on. This decline is due not only to low fertility rates but also to the stagnant and even decreasing life expectancies experienced from 1960 to the beginning of the 21st century. Brent Peabody wrote recently on a foreign policy website that “Rather than being purely a limiting factor, it’s possible to argue Russia’s weak demographic hand has made it even more dangerous. After all, Russia’s need for more people is no doubt a motivating consideration for its current aggressive posture toward Ukraine.”[7] As Bruno Tertrais mentions in his article, written 10 days before the Russian invasion, the interest of Russia in Ukraine is rooted in “the underlying fear that Russia will be absorbed by Asia. A ‘demographic insecurity.’”[8]

Shrinking pre-war Ukraine population

Contrary to other middle-income and developed countries, Ukraine’s last traditional census occurred in 2001; in 2019, this country conducted an electronic census that most national researchers considered inadequate.[9] However, by combining data from different sources, demographers from Ukraine and abroad successfully identified some of the main characteristics of trends occurring after 1990. From this analysis it is clear that, antecedent to the war, Ukraine was experiencing a debilitating demographic moment. The population of Ukraine has been shrinking since 1990, when it attained its maximum of 51.6 million inhabitants. By 2022, the United Nations (UN) estimated that the population of Ukraine would be 43,792,000, but the UN Population Division includes the population within the recognized boundaries of Ukraine (including the Crimea and Donbas regions). Using these data, it is estimated that between 1990 and 2022 Ukraine would have lost about 10.7 million people (more than 20% of its population), while Russia lost 1.3% of its population. However, if the population assessment of Ukraine conducted in 2019 by the Statistical Office[10] is accurate, the actual population size of Ukraine would be even smaller than the 43.8 million estimated by the United Nations: Only around 37.9 million. Accordingly, directly prior to the war, the demographic crisis of Ukraine caused by Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the occupation of the Donbas region, and emigration and low fertility, would have caused a decline of the population of his country of more than 26% between 1990 and 2022.

Apart from the annexations by Russia, this decline in Ukraine’s population was caused by low fertility rates, lower than those of Russia (In 2015–2020, the fertility rate in Ukraine was 1.4 children per woman compared to the Russian rate of 1.8 children per woman), and extremely low and even negative immigration rates from 1995–2005. Ukrainian fertility has been one of the lowest in the world, and there is no expectation that it will increase substantially,[11] even as the result of a post-war baby boom.[12]

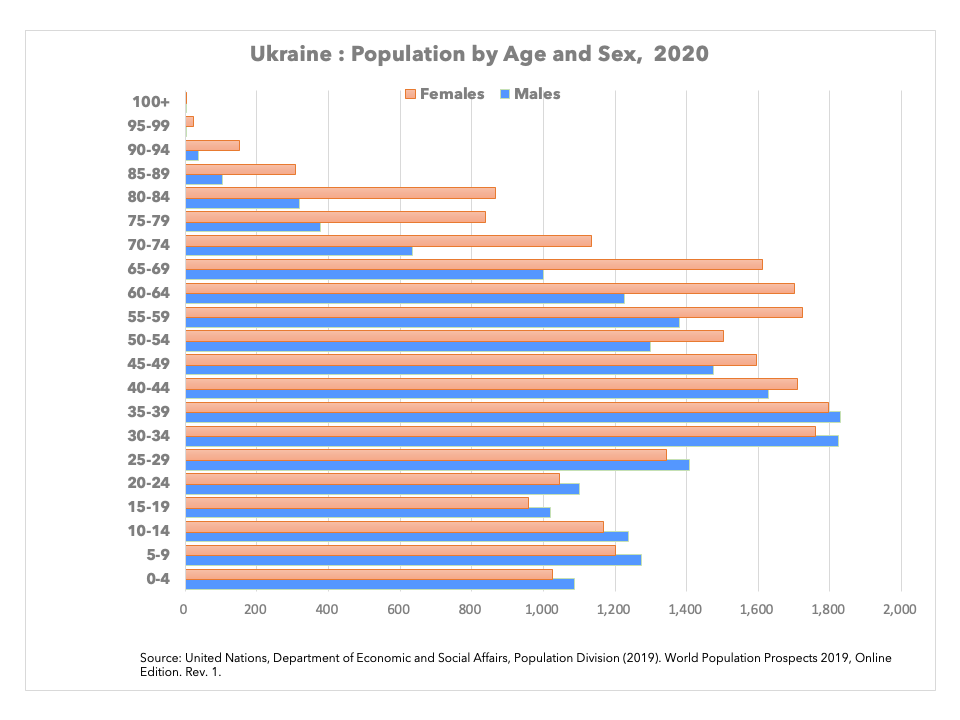

In addition to its decreasing population, Ukraine was rendered further demographically vulnerable, even during the pre-war period, by its population’s sex and age structure. The country’s age structure is characterized by a small number of children and young people relative to the older generation, which implies that fewer women would be entering the reproductive age during the next few years. This factor would problematize the country’s demographic recuperation after the war, as even if women continue to have the same average number of children, fewer women in these ages means fewer births now and in the future; the result is a downward spiral of demographic decline.

The graph of the population by age appears to present two different demographic profiles: one for people aged 40 years and above, born when the country had a fertility rate over the level of replacement (more than two children per woman), and another when fertility continued to decline and reached a rate of 1.2 children per woman by 2020.[13] The number of males aged 15–19 years is almost half the total number of males aged 35–39 years. Additionally, the county has a deficit of males, particularly after the age of 40 years, as can be seen in the figure above. The UN[14] estimates show that by 2020 there would be 23% more females than males aged 40–69 years.

Demographic impacts of war

The current population of Ukraine is now even more reduced, as all the elements that can create a demographic catastrophe are present: an excess of war-related deaths, extreme internal mobility, an increase in emigration (refugees), fewer births, and probable loss of territory. In one of the most accurate and complete studies of the possible demographic impacts of the war, conducted with funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020, Hill Kulu and collaborators[15] conclude that based on the impacts of war casualties and the assumption that only 10% of refugees return home after the war finishes,[16] the population of Ukraine could be reduced by either 24% or 33%, depending on whether the war is short or long. The effect will be felt particularly by the children and working-age populations. As the authors acknowledge, this calculation does not consider additional issues, such as increased mortality due to the long-term effects of the health crisis among the civil population resulting from injuries, infectious diseases, and other traumas augmented by the war.

The situation qualifies as a demographic tragedy for several reasons, the first of which is the loss of lives. Even before the war, Ukraine was not progressing in terms of its population’s life expectancy. While in Poland life expectancy increased by 7.3 years for women and 8.4 years for men between 1990 and 2020, these figures were, respectively, only 1.4 and 0.8 in Ukraine,[17] particularly due to the reduction in this indicator at the beginning of the 1990s and the effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 on the 2020 life expectancy. The war has exacted an unknown number of deaths in both the civil and military Ukrainian population as accurate data is not available. Numbers varies depending on the sources[18].

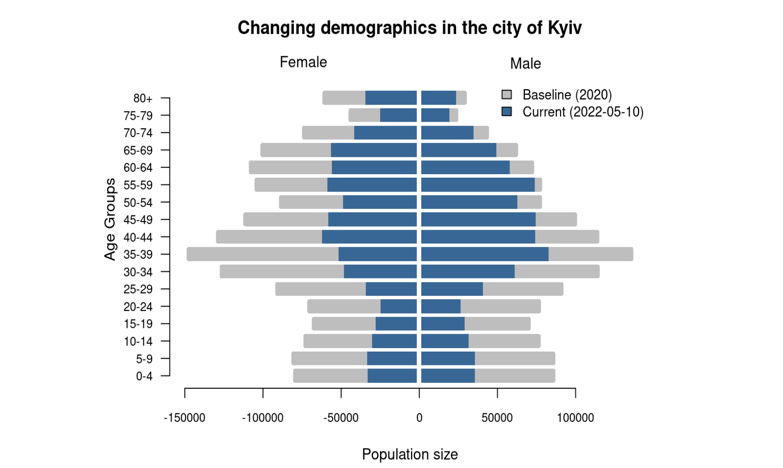

The second factor is the war’s impact on the spatial distribution of the population, which has been continuously and completely altered due to the ongoing massive internal population displacement. The International Organization for Migration estimates that over 7.1 million people, about 16% of the country’s population, have been internally displaced.[19] Although 4.5 million have returned to their place of origin, some could move again if the situation deteriorates. A detailed calculation of displacements between oblasts that was performed based on real-time Facebook penetration rates data combined with demographic data and geospatial methods estimated that by May 15, 2022, 6,842,151 people had been displaced from their baseline oblast.[20] The age structure of the population has been severely affected, with a high proportion of women of all ages and children and adolescents leaving their oblasts (refer to the graph depicting the situation of Kyiv).

Third, a massive number of refugees are fleeing Ukraine to other countries, leaving behind their property, schools, jobs, and other family members. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which is the UN refugee agency, the number of refugees fleeing Ukraine since February 24, 2022 is estimated at 6.6 million.[21] The same agency estimates that during the same period, 2.1 million Ukrainians entered Ukraine, which can be considered a rough estimate of the number of Ukrainians who initially returned to their country once the situation improved in some areas. It is impossible to estimate how many of the refugees will return because this statistic will depend on many other factors, including how long the war lasts, its intensity in the refugees’ areas of residence, and the country’s situation when the war ends. The likelihood that Ukrainians will (or will be able to) return to their residences will be low in areas occupied by Russia, such as the Donbas region. The composition of the returning population will also influence the population’s sex and age structure and the prospect for an increase in population growth.

The fourth factor is the further reduction of fertility directly resulting from the consequences of the war and the possibility of birth rates continuing to decline due to a decrease in the number of women of reproductive age. Additionally, the future uncertainties created by the war may make the decision of having children even harder for women and couples in the future. Louis March asserts that “precious future generations will go unborn because of the slaughter.”[22]

The fifth element is the impact of a population structure with a high proportion of older persons. Even without quality data on the age structure of the refugee population that has left the country or the probable age structure of those who will eventually return to Ukraine, there is a high probability that as refugees are overrepresented by younger people and children, the new age structure of the country will contain fewer people of younger ages and relatively more older individuals. The resulting composition of the population will place greater pressure on the Ukrainian economy during the reconstruction process.

Sixth, the loss of territory due to Russian occupation will significantly impact Ukraine’s population. It is currently estimated that Russian forces occupy about 100,000 square kilometers, including Crimea, which equals around one-fifth of Ukraine’s territory.[23]

The short-term demographic effects of the war in Ukraine are already existent, and they are devastating for a country that was already weak in terms of its demographic profile. Although the long-term effects are unpredictable, the prospect of a continuing demographic tragedy will be difficult to avoid. However, this is not only a demographic tragedy; it is a human tragedy. While this war will likely not be a second Holodomor for Ukraine if measured by the number of deaths, its impact will probably be worse due to the effects of the war and the future expectation of having a such destructive power as a neighbor.

By conducting a merciless military intervention aimed at achieving, among other outcomes, its own demographic expansion, Russia may have desired to demonstrate, as a continuation of a war against Ukraine that started in 2014 with the Euromaidan,[24] the unviability (including demographically speaking) of Ukraine as a nation. Nevertheless, the war has come to demonstrate the opposite, as shown by the emergence of a national spirit and identity under the leadership of President Volodymyr Zelensky. It can be hoped that the demographic resilience of the country, which has been pushed to the limit by the Russian invasion and war, is reinforced and strengthened by this spirit and that new Ukrainian generations can build the future they deserve in a demographically flourishing country.

A more positive demographic outlook, needed for the economic recuperation and reconstruction of the country, should be based on a set of policies and actions which may include at least these three elements: a) a recuperation of fertility rates based on reinforcing gender equity and building family support, b) vast investments in health and mortality reduction and human capital, and c) an audacious immigration policy that will draw workers and families from other countries to fill the gaps in the population’s age and sex structure and bring and sustain the new labor supply structure, sufficient in numbers and skills, needed to rebuild the country. In its reconstruction as a resilient and stronger country, the contribution that demography can make to Ukraine will be an essential part of the solution.

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank the following persons who contributed with comments and suggestions to this article: Mikhail Minakov, the Wilson Center Kennan Institute’s Senior Advisor on Ukraine and Editor-in-Chief of Focus Ukraine, which is Kennan Institute’s Ukraine-focused blog; Jaime Nadal Roig, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Country Representative for Ukraine; Ilona Sologoub, Scientific Editor of VoxUkraine; Andy Tatem, Founder and Director of WorldPop and Professor of Spatial Demography and Epidemiology at University of Southampton; Ritika Puri, COO and co-founder Storyhackers; and Mónica Villarreal, Co-founder of NoBrainerData.

- Unless stated differently, data used in this analysis comes primary from State Statistics Service of Ukraine. http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/ Accessed on June 2, 2022)

- Romaniuk, A., & Gladun, O. (2015). Demographic Trends in Ukraine: Past, Present, and Future. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 315–337. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24639360

- Ibidem.

- Putin the Great? Russia’s President Likens Himself to Famous Czar. June 9, 2022 Anton Troianovski. New York Times. June 9, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/09/world/europe/putin-peter-the-great.html

- Vladimir Putin’s annual news conference, 2019. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/62366 .

- See also https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/12/01/russia-population-decline-putin/

- Russia Doesn’t Have the Demographics for War: The 1990s collapse in birth rates still impacts Moscow’s ambitions.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/03/russia-demography-birthrate-decline-ukraine/ - Why Ukraine Matters to Russia: The Demographic Factor. https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/why-ukraine-matters-russia-demographic-factor Accessed on May 30, 2022.

- Ukraine’s census attempt crashes and burns yet again. Independent Ukraine has held only one census, almost 20 years ago. Mariya Chukhnova Aug 12, 2020. https://eurasianet.org/ukraines-census-attempt-crashes-and-burns-yet-again

- https://www.rbc.ua/ukr/news/nazvana-chislennost-naseleniya-ukrainy-1579768750.html

- Only 6 per cent of Ukrainians would be thinking in having one child in the near future (Michał Kozak. The Ukraine’s population is lower than previously believed 29.06.2020. https://www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl/autor/michal-kozak/

- “I’m not convinced of a sharp spike in post-war birthrates in Ukraine” said Ella Libanova, Director of the Ukrainian Institute of Demography and Social Sciences, when asked if we could expect a baby boom following the war. Interview with sociology professor on how the war will impact Ukraine’s demographics. Author: Ирина Крикуненко. https://english.nv.ua/nation/interview-with-sociology-professor-ella-libanova-on-war-s-effect-on-ukraine-s-demographics-ukraine-50248230.html

- Data from State Statistics Service of Ukraine shows that fertility did not show a steady decline during the period 1990-2020, having a first decline up to 2001, when total fertility rate was close to 1 child per woman, increases again to 1.5 observed between 2000 and 2008 and then decline again to 1.2 children per woman. It is possible that these oscitations are more ‘tempo’ effects than real changes in the final number of children women have.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1.

- Kulu, H., Christison, S., Liu, C., & Mikolai, J. (2022). The War and the Future of Ukraine’s Population. MigrantLife Working Paper 9. http://migrantlife.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2022/03/The-War-and-the-Future-of-Ukraines-Population.pdf

The number of women of reproductive age had already declined steadily from 12 million in 2008 to 8.8 million in 2021. - This could probably happen only if the war situation deteriorates in such a way that people cannot return even if they want, as surveys shows that close to 80 % of refugees want to return after the war. Razumkov Center. Ukrainian refugees: attitudes and assessments (March 2022). https://razumkov.org.ua/napriamky/sotsiologichni-doslidzhennia/ukrainski-bizhentsi-nastroi-ta-otsinky?fbclid=IwAR0-vmzoi0oebP8E5z0dUQli4be9hqASb2KhvWYiwNjruTuxAfQxK9P7e48

- Based on estimates provided by the United Nations. United Nations. 2019 Revision of World Population Prospects. https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/

- The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights estimate that by June 3, the number of civilian casualties in the country include 4,183 killed and 5,014 injured. https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2022/06/ukraine-civilian-casualty-update-3-june-2022

- Ukraine — Internal Displacement Report — General Population Survey Round 5 (17 May 2022- 23 May 2022) Accessed on April 30, 2022.

- Leasure DR, Kashyap R, Rampazzo F, Elbers B, Dooley CA, Weber I, Fatehkia M, Bondarenko M, Verhagen M, Frey A, Yan J, Akimova ET, Sorichetta A, Tatem AJ, Mills MC. 2022. Ukraine Crisis: Monitoring population displacement through social media activity, v3.0. Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science, University of Oxford; SocArXiv. 16 May 2022. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/6j9wq

- UNHCR Operational Data Portal. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine Accessed on May 24. Accessed on May, 2022.

- Ukraine’s other battle: demography. Mercatornet. by Louis T. March. Mar 17, 2022.

https://mercatornet.com/ukraines-other-battle-demography/78094/ - How the map of Ukraine has changed in three months of war. El Pais. International. Accessed on May 30, 2022. https://english.elpais.com/international/2022-05-24/how-the-map-of-ukraine-has-changed-in-three-months-of-war.html

- See https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/understanding-ukraines-euromaidan-protests

Brilliant and utterly fascinating analysis. Congrats Jose Miguel

Dear Sir. Dear Jose Miguel Guzman. I think it is time to dump all of your old text books. Your article / study is full with old and extremely stupid ideas. Ukraine 150 km from my home in Hungary, is in war now, and mortality-displacement was on, just as strongly as in Russia, and all other advanced economies. Mortality-displacement is when countries have high portion of residents over 55 years old … The whole point of my response is this, Ukraine with Russian assistance will eventually “kill” all of its over 55 population, and will gain the youngest -by far- population within Europe. The question is then rather this: Haw fast the west will capture its new demographic dividend… ????

You may ask why ? Well, most of the world 140 million babies are produced by the shrinking percentage of earth human population of 8 billion. They are called fertile-women between the age of 20-30, today. They used to represent about 12 percent of the total population before the pills, now they are only about 6 or 5 percent- except Africa -… This not the result of the pill, rather the result of the financial system. That system created the illusion to you that you and I, and many more of us can have a meaningful life over 65 too. No it is false.. I am 63… But I see, that we create the next war, and the next after that… “War is young men dying and old men talking.” — Franklin D. Roosevelt..

Well at times, old men are just imposing. Young men are blindly following, Stop being blind,… please.

Soviet Ukraine was 52 million happy people. Current fascist Ukraine is 20 million desperately unhappy people, 10 million of them are old pensioners. Thank you, West, for democratization! Wish you the same!